In recent years, the phrase ranked-choice voting (RCV) has been popping up in conversations about elections, democracy, and political reform. From local city councils to state legislatures, and even in discussions about national elections, RCV is gaining traction as an alternative to traditional voting systems. But what exactly is it, why are people talking about it, and is it really the game-changer its advocates claim? Let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of ranked-choice voting, explore its history, weigh its pros and cons, and see where it’s being used today.

What Is Ranked-Choice Voting?

Ranked-choice voting, sometimes called instant-runoff voting (IRV) in single-winner elections, is a voting system where voters rank candidates in order of preference rather than picking just one. Instead of casting a single vote for your favorite candidate, you get to list your first choice, second choice, third choice, and so on. If no candidate wins a majority (over 50%) of first-choice votes, the system kicks into gear with a process that eliminates candidates and redistributes votes until a winner emerges.

Here’s how it works in a single-winner election:

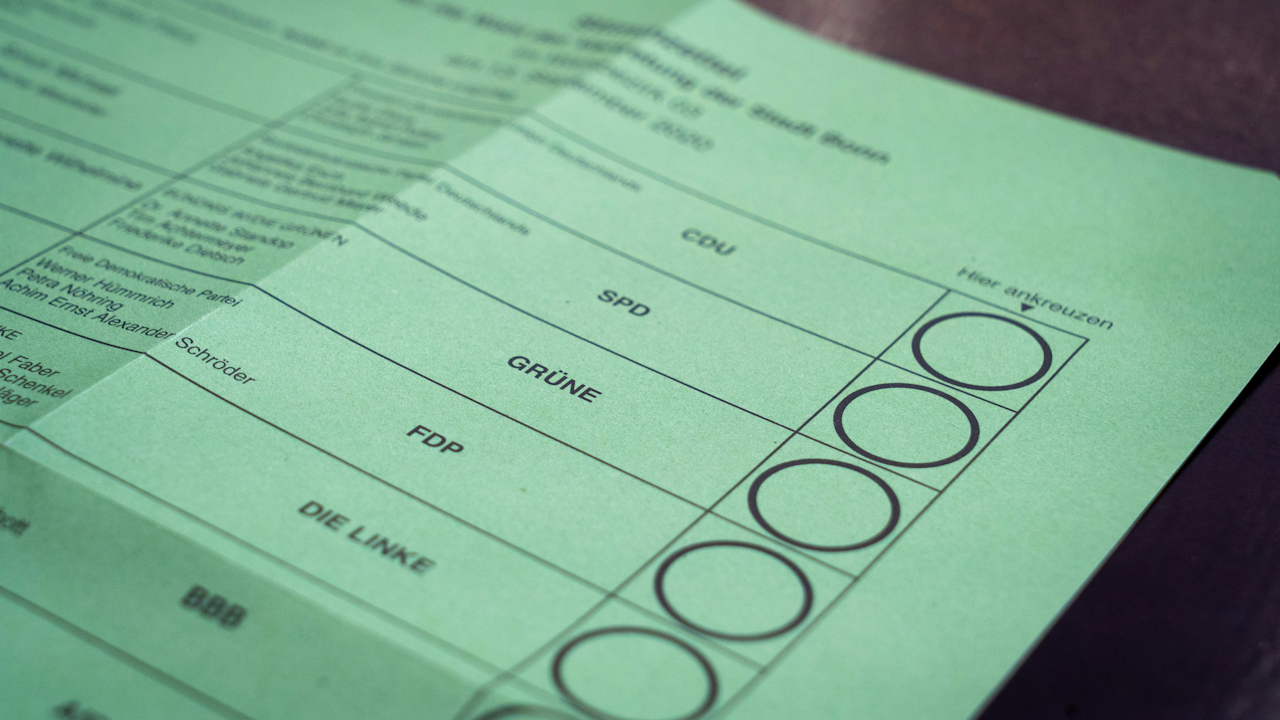

- Voters rank candidates. On the ballot, you mark your top choice as “1,” your second choice as “2,” and so forth. You can rank as many or as few candidates as you want, depending on the rules.

- First-round count. Election officials tally all the first-choice votes. If a candidate gets more than 50% of the votes, they win outright, and the process ends.

- Elimination and redistribution. If no candidate hits the majority threshold, the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated. Their votes are redistributed to the voters’ second choices. This process repeats—eliminating the lowest vote-getter and redistributing votes—until someone gets a majority.

- Winner declared. Once a candidate crosses the 50% mark (or the field is narrowed to two candidates in some systems), they’re declared the winner.

For multi-winner elections, like city councils or legislatures, RCV can be adapted to allocate seats proportionally, but the single-winner version is more common in the U.S.

The system sounds simple enough, but it’s a big departure from the plurality voting most of us are used to, where the candidate with the most votes wins, even if they don’t get a majority. That traditional setup can lead to some quirks—like a candidate winning with 30% of the vote in a crowded race, even if 70% of voters preferred someone else. RCV aims to fix that by ensuring the winner has broader support.

A Brief History of Ranked-Choice Voting

Ranked-choice voting isn’t a newfangled idea cooked up by political nerds in a think tank. It’s been around for over a century. The concept traces back to the 19th century, with early versions proposed by mathematicians and reformers like Thomas Hare in England and Carl Andrae in Denmark. It gained traction in the 1860s and was first used in Australia in the early 20th century for federal elections. Australia’s been using RCV (or similar systems) ever since, making it one of the longest-running case studies.

In the United States, RCV had a brief heyday during the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), when cities like Cleveland, Cincinnati, and New York City experimented with it to combat machine politics and ensure fairer representation. But by the mid-20th century, many of these experiments were rolled back, often because political machines didn’t like how RCV disrupted their control.

The modern resurgence of RCV began in the early 2000s, with cities like San Francisco and Minneapolis adopting it for local elections. Since then, it’s spread to other places, fueled by frustration with polarized politics, “spoiler” candidates, and unrepresentative outcomes. By 2025, RCV is used in over 50 jurisdictions across the U.S., including major cities and even entire states for certain elections.

Why Do People Like Ranked-Choice Voting?

Advocates of RCV argue it solves a bunch of problems with traditional voting systems. Here are the main reasons it’s got fans:

1. It Reduces the “Spoiler” Problem

In plurality voting, third-party or independent candidates can split the vote, letting a less popular candidate sneak through. Think of a race where two liberal candidates split 60% of the vote, letting a conservative candidate win with 40%. RCV fixes this by letting voters rank their preferences. If your favorite third-party candidate gets eliminated, your vote isn’t “wasted”—it goes to your second choice.

2. It Encourages Majority Support

RCV ensures the winner has broader appeal. In a crowded field, a candidate who’s nobody’s first choice but everyone’s second or third choice can still win, reflecting a consensus rather than a polarized plurality.

3. It Promotes Civility

Because candidates want to be voters’ second or third choice, they’re incentivized to avoid mudslinging and appeal to a wider audience. In theory, this leads to less negative campaigning and more coalition-building.

4. It Empowers Voters

RCV gives voters more flexibility to express their true preferences without worrying about “wasting” their vote. You can support a long-shot candidate without feeling like you’re throwing away your influence.

5. It Can Increase Turnout and Diversity

Some studies suggest RCV boosts voter turnout by making elections feel more competitive and inclusive. It’s also been credited with electing more diverse candidates in places like San Francisco, where minority groups have gained better representation under RCV.

What’s the Catch? The Case Against RCV

Not everyone’s sold on ranked-choice voting. Critics point out some real and perceived downsides:

1. It’s Complicated

RCV ballots can confuse voters, especially those used to picking one candidate and calling it a day. Ranking multiple candidates requires more thought, and some worry it could lead to errors or disenfranchise less-engaged voters. Studies show voter error rates in RCV elections are low (around 1–2%), but critics argue even small errors can undermine trust.

2. It’s Not Always Intuitive

The process of eliminating candidates and redistributing votes can feel like a black box to the average voter. In close races, the outcome might hinge on how second or third choices shake out, which can seem less straightforward than “most votes wins.”

3. It Doesn’t Always Fix Polarization

While RCV encourages civility, it doesn’t magically bridge ideological divides. In highly polarized races, voters may still rank only candidates from their own “side,” limiting the system’s ability to produce consensus winners.

4. It’s Costly to Implement

Switching to RCV often requires new voting machines, software, or ballot designs, plus voter education campaigns. For cash-strapped local governments, that can be a tough sell.

5. It Can Exhaust Ballots

If a voter only ranks one or two candidates and both get eliminated early, their ballot becomes “exhausted” and doesn’t count in later rounds. In some RCV elections, up to 10–15% of ballots get exhausted, which critics say undermines the “every vote counts” promise.

Where Is Ranked-Choice Voting Used?

As of 2025, RCV is gaining ground but still isn’t widespread. Here’s a snapshot of where it’s in play:

- United States:

- States: Maine and Alaska use RCV for statewide and federal elections, including gubernatorial and congressional races. Maine was the first state to adopt it statewide in 2016, followed by Alaska in 2020.

- Cities: Over 50 cities use RCV, including New York City (for primaries and special elections), San Francisco, Oakland, Minneapolis, and Seattle. New York City’s adoption in 2021 was a big deal, given its massive voter base.

- Other jurisdictions: Some counties and smaller municipalities, like Arlington, Virginia, and Bloomington, Minnesota, use RCV for local elections.

- Internationally:

- Australia: Uses RCV (called preferential voting) for its House of Representatives and some state elections.

- Ireland: Uses RCV for presidential elections and some parliamentary elections.

- New Zealand: Some local elections use RCV, though first-past-the-post still dominates.

- Scotland: Local council elections use a multi-winner version of RCV called the single transferable vote (STV).

Real-World Examples: How RCV Plays Out

To get a sense of RCV in action, let’s look at a couple of examples:

- Maine’s 2018 Congressional Election: Maine’s 2nd Congressional District used RCV for the first time in a federal election. Incumbent Republican Bruce Poliquin led after first-choice votes but didn’t hit 50%. After rounds of redistribution, Democrat Jared Golden pulled ahead and won, thanks to second-choice votes from third-party voters. It showed how RCV can flip outcomes in tight races.

- New York City’s 2021 Mayoral Primary: In the Democratic primary, Eric Adams won after multiple rounds of vote redistribution. The process took days to finalize because of the large number of candidates (13!) and ballots. While Adams likely would’ve won under plurality voting too, RCV gave a clearer picture of voter preferences and avoided a split-vote scenario.

Does It Actually Work?

The evidence on RCV is mixed but promising. Studies from places like San Francisco and Minneapolis show it increases voter satisfaction and reduces “wasted” votes (ballots that don’t contribute to the final outcome). In Australia, RCV has been credited with stabilizing the political system by encouraging coalition-building and reducing the dominance of two major parties.

On the flip side, critics point to cases like the 2021 New York City mayoral primary, where the complexity of counting millions of ballots led to delays and some voter skepticism. There’s also the 2010 Oakland mayoral race, where RCV elected a candidate who wasn’t the first-choice leader, sparking debate about whether the system always reflects the “will of the people.”

The Future of Ranked-Choice Voting

RCV is at a crossroads. Its advocates see it as a cure for many of democracy’s ailments—vote-splitting, polarization, and unrepresentative outcomes. Grassroots campaigns, backed by groups like FairVote, are pushing for its adoption in more states and cities. But resistance remains, especially from entrenched political interests who benefit from the status quo. Some states, like Florida and Tennessee, have even passed laws banning RCV, citing concerns about complexity and cost.

The 2024 U.S. election cycle saw RCV on ballots in several places, with voters in states like Nevada and Oregon weighing whether to adopt it. As of now, the momentum is with RCV’s supporters, but scaling it to national elections—like for president—would require massive logistical and political shifts.

So, What’s the Deal?

Ranked-choice voting isn’t a silver bullet, but it’s a compelling alternative to the way we’ve always done things. It offers a path to fairer, more representative elections, especially in a world where voters are frustrated with polarization and limited choices. But it’s not without flaws—complexity, cost, and the learning curve for voters are real hurdles.

If you’re intrigued, check out what’s happening in your own backyard. Is your city or state experimenting with RCV? Maybe it’s time to rank your preferences and join the conversation.