In the traditional world of conservation, the mantra has long been “bigger is better.” For decades, environmentalists focused on vast national parks and sprawling wilderness reserves as the only viable way to protect the planet. While these massive landscapes are undeniably vital, a new wave of ecological research is revealing that size is not the only factor that matters.

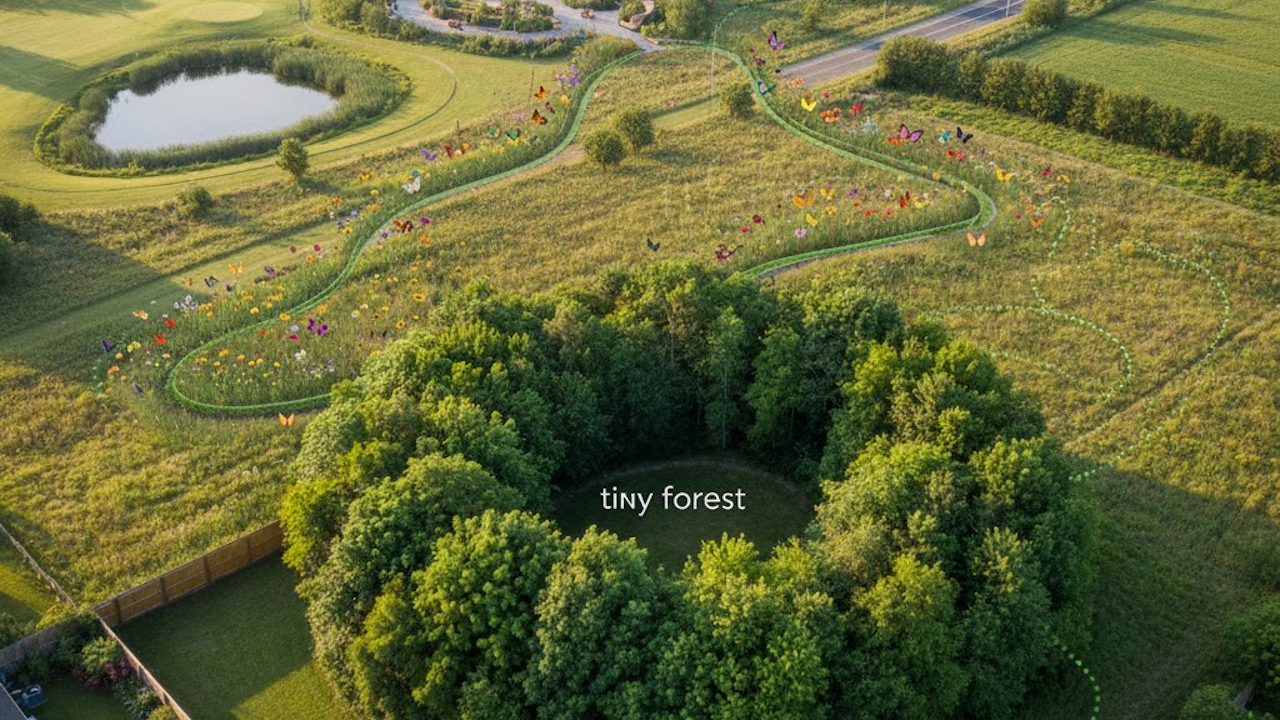

In fact, a patchwork of small, strategically placed spaces is often the silent engine driving the health of the entire planet. From urban “tiny forests” to roadside wildflower strips, these miniature habitats are performing an outsized role in saving large-scale ecosystems.

The Power of the Micro-Reserve

A micro-reserve is a small area of land, often less than twenty hectares, set aside to protect specific species or unique habitat types. While a single small patch may seem vulnerable to local extinction, a network of many small patches provides a unique form of biological stability.

One major advantage is the reduction of total risk. If a disease or a natural disaster strikes one large, continuous forest, the entire population of a species could be wiped out. However, if that same population is spread across twenty different small reserves, it is highly unlikely that all twenty will be affected simultaneously. This “portfolio effect” ensures that even if one patch fails, the others can act as a source of seeds and individuals to repopulate the landscape.

Stepping Stones and Wildlife Corridors

Large ecosystems cannot survive in isolation. Animals need to move to find food, mates, and new territory. As human development carves up the landscape with roads, fences, and cities, wildlife populations become “islands” of genetic stagnation.

Small spaces act as the “stepping stones” that bridge these gaps. A single suburban backyard filled with native plants or a small wetland on the edge of a golf course can serve as a vital pit stop for a migrating bird or a wandering pollinator. These tiny corridors prevent inbreeding and allow species to shift their ranges as the climate changes. Without these small nodes of connectivity, the genetic health of the larger ecosystem would eventually collapse.

Examples of Small-Scale “Stepping Stones”

- Hedgerows: These narrow lines of shrubs between farm fields provide nesting sites and travel lanes for small mammals and insects.

- Pocket Parks: In dense cities, these quarter-acre green spaces offer refuge for migratory songbirds.

- Roadside Verges: Management of the grass along highways can create thousands of miles of continuous habitat for bees and butterflies.

The Miyawaki Method: Tiny Forests with Big Impact

One of the most exciting developments in small-scale conservation is the Miyawaki Method. Named after Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, this technique involves planting a high density of native trees and shrubs in a very small area, sometimes no larger than a tennis court.

Because the plants are packed so closely together, they compete for sunlight, which triggers rapid growth. A Miyawaki forest can grow ten times faster and become thirty times more dense than a traditional plantation. These “tiny forests” act as intense biodiversity hotspots. They absorb massive amounts of carbon dioxide, soak up rainwater to prevent local flooding, and lower the surrounding air temperature by several degrees. By cooling cities and cleaning the air, these small plots support the broader regional climate systems.

Economic and Social Spillover

The benefits of small spaces extend beyond biology into the human economy. Small-scale restoration projects are often more cost-effective than managing massive tracts of land. They allow local communities to take direct ownership of their environment, fostering a culture of stewardship that is harder to achieve with distant national parks.

Furthermore, small reserves often create a “spillover effect.” For example, a small no-take marine reserve can lead to a massive increase in fish populations in the surrounding waters where fishing is allowed. Similarly, a small urban wetland can naturally filter pollutants from runoff before they reach larger rivers and oceans, saving municipalities millions in water treatment costs.

Rethinking the Map

To save our large ecosystems, we must start looking at the gaps between them. Every vacant lot, every school garden, and every narrow strip of riverbank is a potential engine for ecological recovery. We no longer have the luxury of waiting for the next million-acre wilderness to be saved. Instead, we must build a resilient future one small space at a time.