Beauty standards shape how people see themselves, how they judge others, and even how they move through society. Although these standards often appear natural or objective, they are produced and reinforced by complex psychological forces. Understanding these forces helps explain why beauty ideals change across cultures and eras, yet still hold enormous power. It also helps clarify why people internalize such ideals even when they know they are unrealistic. The psychology of beauty standards involves perception, identity, social comparison, reward mechanisms in the brain, and cultural conditioning that starts at an early age and persists throughout adulthood.

Human perception plays an important role because the brain is wired to notice certain patterns. Researchers often point to universal cues such as facial symmetry, skin clarity, or certain body proportions that people across cultures tend to find attractive. These cues may signal health or fertility, which explains their potential evolutionary value. However, these biological biases interact with cultural messages that magnify or distort them. A society might emphasize thinness, muscularity, height, specific facial features, or particular skin tones, none of which are universally preferred. As a result, people often mistake culturally specific ideals for natural truths. The brain becomes trained to perceive these traits as desirable simply because exposure is frequent and consistent.

Identity formation is another key psychological factor. During childhood and adolescence, people look to external cues to define who they are and how they fit into their social environment. Beauty standards offer a visible set of rules that promise acceptance and status when followed. Young people who receive praise for conforming to beauty norms learn to connect their physical appearance with self worth, while those who do not meet these expectations may struggle with insecurity or exclusion. Over time, these experiences become ingrained in a person’s self concept. Even as adults they may continue to evaluate themselves through the lens of beauty norms learned early in life.

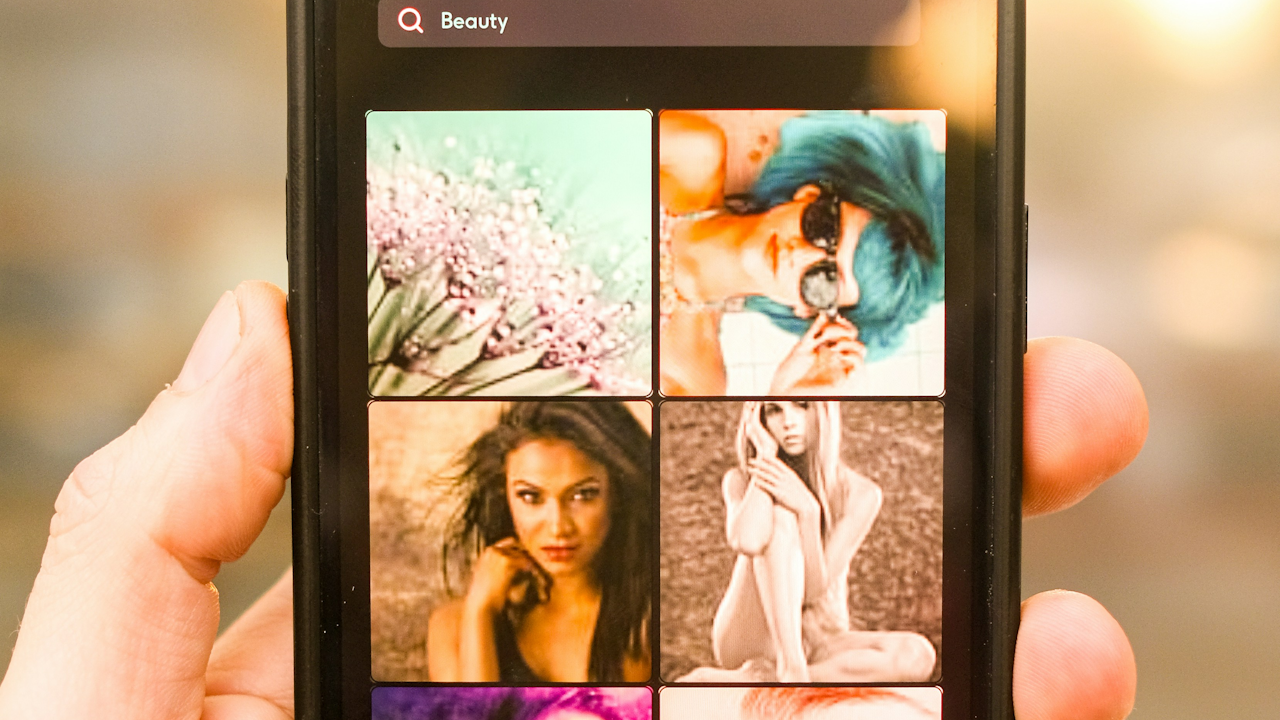

Social comparison makes this process even stronger. People constantly evaluate themselves relative to others, especially in areas that society deems important. When beauty is framed as a central measure of value, comparison becomes almost unavoidable. Media plays a major role here because it exposes people to a narrow set of idealized images. Whether through magazines, television, advertising, or social platforms, these images create unrealistic reference points. People compare themselves to curated and edited representations rather than to real individuals. This can lead to chronic dissatisfaction and distorted self perception. Even when people understand consciously that images are manipulated, the emotional impact remains.

Reward systems in the brain also reinforce beauty norms. Individuals who match cultural ideals often receive positive feedback such as attention, compliments, or social privileges. These interactions trigger dopamine responses that strengthen behaviors aimed at maintaining or enhancing appearance. In contrast, negative reactions or exclusion can reinforce a sense of inadequacy. Over time the pursuit of beauty becomes tied to the desire for social reward and the avoidance of social pain. This helps explain why people invest significant energy, time, and resources into meeting beauty expectations even when they know these efforts may be harmful.

Cultural conditioning plays a powerful role in shaping what is considered attractive. Beauty ideals are transmitted through family values, peer groups, and media messages. They are also influenced by socio economic factors, political systems, and historical events. For example, economic prosperity can shift ideals toward bodies that signal leisure or abundance, while scarcity can shift them toward bodies that suggest discipline or resilience. In many societies skin tone preferences have roots in colonial histories or class structures, revealing how beauty standards can reflect power dynamics. These cultural influences operate subtly yet consistently, making the standards appear natural even when they are deeply constructed.

The intersection of these psychological forces contributes to significant mental health impacts. Individuals who feel pressured to conform may experience anxiety, depression, body dysmorphia, or low self esteem. The gap between idealized images and typical human variation creates a sense of failure for many people. This can lead to extreme dieting, over exercising, cosmetic procedures, or avoidance of social situations. The psychological burden is not distributed evenly. Women, for example, often face more intense scrutiny related to appearance. At the same time men are increasingly affected by pressures around muscularity or youthfulness. People of color encounter additional challenges when dominant beauty norms favor traits associated with other racial groups.

Despite the weight of these forces, beauty standards are not fixed. They evolve as cultures change and as people challenge narrow or harmful ideals. Social movements promoting body diversity, natural hair, skin tone inclusivity, and age representation help broaden the definition of beauty. Psychological research shows that exposure to diverse images can shift perceptions and reduce the dominance of a single ideal. Education about media literacy also helps people recognize manipulation and resist unhealthy comparison.

Ultimately, understanding the psychology of beauty standards reveals how much influence culture has over what individuals believe about themselves. It shows that while attraction has some biological roots, most beauty ideals are learned, reinforced, and changeable. Recognizing this can empower people to think critically about the messages they absorb and to build identities that rely on more than appearance. When societies embrace a broader range of beauty, individuals benefit mentally and emotionally, and the collective understanding of human worth becomes richer and more compassionate.