In recent years, political and social polarization has grown sharper in many parts of the world. People increasingly find themselves living in ideological bubbles, surrounded by those who share their views and rarely engaging meaningfully with those who see the world differently. This separation affects communities, workplaces, and even families. The question arises: can dialogue bridge the widening gaps, or are these divides too deep to overcome?

The Nature of Polarization

Polarization is not simply disagreement. Healthy disagreement can lead to innovation, better decision-making, and stronger democratic processes. Polarization occurs when disagreement becomes entrenched and emotionally charged, turning into an “us versus them” mindset. In such an environment, the opposing side is not just wrong but is viewed as morally flawed or even dangerous. Once this thinking sets in, constructive discussion becomes difficult because each side assumes the other is acting in bad faith.

Social media and digital communication have amplified these divisions. Algorithms often prioritize emotionally charged content, rewarding outrage and conflict. Traditional media outlets can also contribute, sometimes reinforcing partisan narratives rather than fostering understanding. As a result, many people rarely encounter views that challenge their own, and when they do, the exposure is often filtered through caricatured portrayals.

Why Dialogue Matters

Dialogue offers a way to counteract these forces. At its core, dialogue is not about winning an argument or proving a point. It is about listening actively, asking questions, and seeking to understand the perspective of another person. This process humanizes the “other side” and can reduce the emotional hostility that fuels polarization.

Studies in social psychology have shown that when people feel heard and respected, they become more open to considering alternative perspectives. This does not necessarily mean they will change their minds on deeply held beliefs, but it can lead to a more constructive and respectful exchange. Over time, such exchanges can build trust, which is an essential foundation for addressing divisive issues.

Challenges to Productive Dialogue

While dialogue holds promise, it is not a cure-all. In highly polarized environments, engaging with someone on the opposite side can feel risky. People worry about being judged, attacked, or misunderstood. There is also the challenge of asymmetry: some groups may feel that their very rights or safety are under threat, making dialogue feel like an unequal burden. In such cases, asking people to simply “talk it out” can seem dismissive of real grievances.

Another difficulty is that dialogue requires time, patience, and emotional effort. Quick exchanges on social media are unlikely to foster meaningful understanding. In-person or extended virtual conversations offer more potential, but they demand commitment and a willingness to listen without immediately rebutting.

Approaches That Show Promise

Several initiatives have demonstrated that dialogue, when carefully structured, can lead to significant breakthroughs. Programs that bring together people from opposing political, religious, or cultural backgrounds often begin with ground rules that ensure mutual respect. Participants may start by sharing personal stories rather than debating policy. Storytelling helps shift the conversation from abstract issues to lived experiences, making it harder to dismiss another person’s perspective outright.

Another promising approach is “deep canvassing,” where volunteers engage in extended, non-judgmental conversations with people about contentious issues. Instead of delivering talking points, they listen, share personal experiences, and explore the reasons behind someone’s views. Research has found that this method can create lasting shifts in attitudes, especially when it addresses topics tied to prejudice or misinformation.

Dialogue also benefits from facilitation. Trained moderators can help keep conversations constructive, ensure that everyone has a chance to speak, and gently redirect discussions that become heated. Without this structure, there is a risk that a dialogue session could devolve into the same combative exchanges that happen online.

The Role of Institutions

While individual conversations matter, institutions also play a critical role in fostering dialogue. Schools, workplaces, and community organizations can create spaces where people feel safe to share their views and engage across divides. Media outlets can contribute by highlighting stories of cooperation and bridge-building rather than focusing solely on conflict.

Governments can support dialogue through public forums and citizen assemblies, where diverse participants come together to deliberate on policy issues. Such assemblies have been used successfully in places like Ireland to address deeply divisive topics such as same-sex marriage and abortion. By structuring the process to encourage listening and mutual respect, these forums can produce recommendations that reflect a broader consensus than might be expected.

Limitations and Realism

It is important to acknowledge that dialogue is not a magic solution. Some divides are rooted in systemic inequalities that cannot be resolved through conversation alone. Dialogue may help build understanding, but it must be accompanied by concrete actions that address underlying grievances. Without tangible change, dialogue risks being perceived as performative or insincere.

Moreover, not every situation calls for engagement. In cases where one side denies the basic humanity of another, the priority may need to be safety and justice rather than conversation. Dialogue works best when there is at least some shared commitment to living together peacefully, even if values and beliefs differ.

A Way Forward

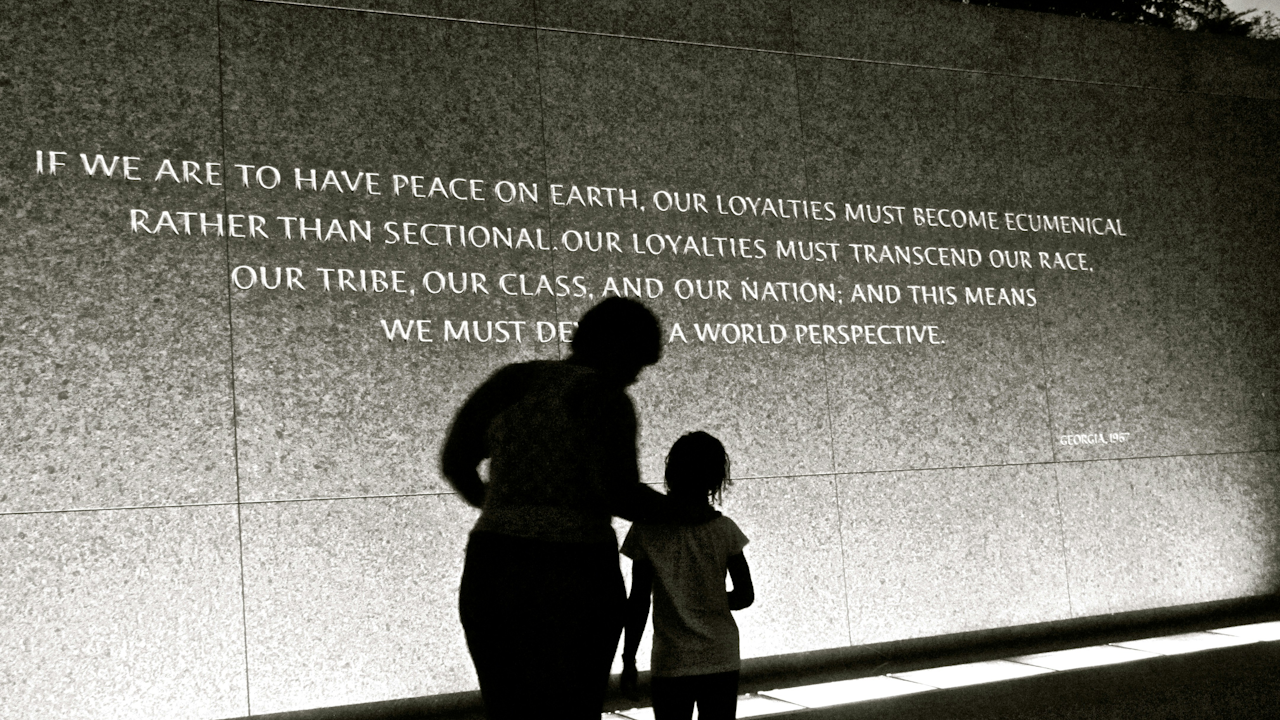

Despite these limitations, the potential of dialogue should not be dismissed. It offers a way to begin breaking down the walls of distrust that fuel polarization. This does not require every conversation to end in agreement, but it does require a willingness to see the other person as more than a stereotype. Even small shifts in perspective can ripple outward, influencing how communities and societies navigate their differences.

In an age where divisions feel intractable, dialogue is both a modest and a radical act. It is modest because it begins with something as simple as listening. It is radical because it challenges the patterns of separation and suspicion that dominate public life. Healing deep divides will require many tools, but without dialogue, it is difficult to imagine lasting reconciliation.